Update: This article describes my initial thoughts on a proportional voting system involving exactly two MPs per riding. I later found out about Dual Member Proportional (DMP) a fully developed system similar in essence to the one described here.

If there’s one change Canadians want to see in our electoral system, it’s a little more proportionality. According to a recent Abacus Data survey1, Canadians would prefer a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system to ranked ballots. The survey participants also favoured the goal that “the number of seats held by a party in Parliament closely matches their actual level of support throughout the country” to other electoral changes such as ensuring MPs have majority support in a district, electing more women and people with diverse backgrounds, or electing more independents. If Canada’s voting system were to change, yet fail to move even slightly in the direction of proportional representation, the reform would be regarded as disappointing at best.

Nevertheless, many Canadians have raised concerns about proportional representation, including the current Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau2. Among the concerns is the idea that proportionality will weaken ties between MPs and the local communities they are compelled to serve under the current First Past the Post system. According to a policy resolution posted by the governing Liberal party, Canadians want MPs to be “effective voices for their communities”, not “mouthpieces in their communities […]”3, and to some extent the Abacus Data survey supports this claim. Of the 15 goals included in the survey, the general principle of proportionality placed 5th, while community representation placed 3rd. The relationship between MPs and communities is highlighted below in the list of top five goals as reported by Abacus Data:

- The ballot is simple and easy to understand.

- The system produces stable and strong governments.

- The system allows you to directly elect MPs who represent your community.

- The system ensures that the government has MPs from each region of the country.

- The system ensures that the number of seats held by a party in Parliament closely matches their actual level of support throughout the country.

The relative importance of community representation versus proportional representation continues to be debated in a number of forums. I would like to side-step the debate by searching for a solution that addresses both priorities. The evidence is clear that community representation matters to Canadians. But it is equally clear that if we are to reform our system, proportional representation is the direction we want to go. So how does Canada steer toward proportionality while still requiring all MPs to serve communities and win their constituents’ support?

My proposed solution is called Cooperative Proportional. It’s a new voting system which features two MPs in every riding. The first MP is elected in a traditional First Past the Post manner. The second MP is elected based on the popular vote. The system was first introduced in a preceding article4, in which I explain how election outcomes would become proportional. I now refine the system to further emphasize community representation. The refinement is based on the 20% rule, a requirement that the second MP in each riding receives at least 20% as many votes as the first MP. The main purpose of the 20% rule is to ensure that this second MP, the one elected based on proportionality, has both a mandate to speak for his/her constituents and the incentive to serve them.

The remainder of this article outlines the refined version of Cooperative Proportional. I explain how the system satisfies Canadians’ top five goals as reported in the Abacus Data survey. The discussion progresses upward from the 5th most popular goal.

Goal #5: The system ensures that the number of seats held by a party in Parliament closely matches their actual level of support throughout the country.

In 1993, Canada’s Progressive Conservative party won more than 16% of the popular vote, but was awarded less than 1% of the seats in the House of Commons. In 2008, the Green party won nearly 7% of the popular vote, but was denied even a single seat. With a purely proportional system, the Progressive Conservatives would have won 47 of the 295 seats in 1993, and the Green party would have received 21 of the 308 seats in 2008. For reasons we will discuss, very few systems are purely proportional. Multi-Winner Single Transferable Vote (STV), for example, might not have given the Progressive Conservatives the full 47 seats needed to match their actual level of support. But STV would have given them many more than 2 seats, so it’s one of several voting systems that could take Canada closer to proportionality. Cooperative Proportional is another such system.

As mentioned, Cooperative Proportional elects two MPs in every riding. The first MP is the one who wins the most votes. He/she is called the representative. The second MP, the co-representative, is selected in a way that adjusts the overall distribution of seats in the House of Commons to reflect the popular vote. When determining the co-representatives, the voting system favors candidates who receive substantial support within their ridings. Often the 2nd-place finisher will become the co-representative, though in some ridings it will be the 3rd– or 4th-place finisher.

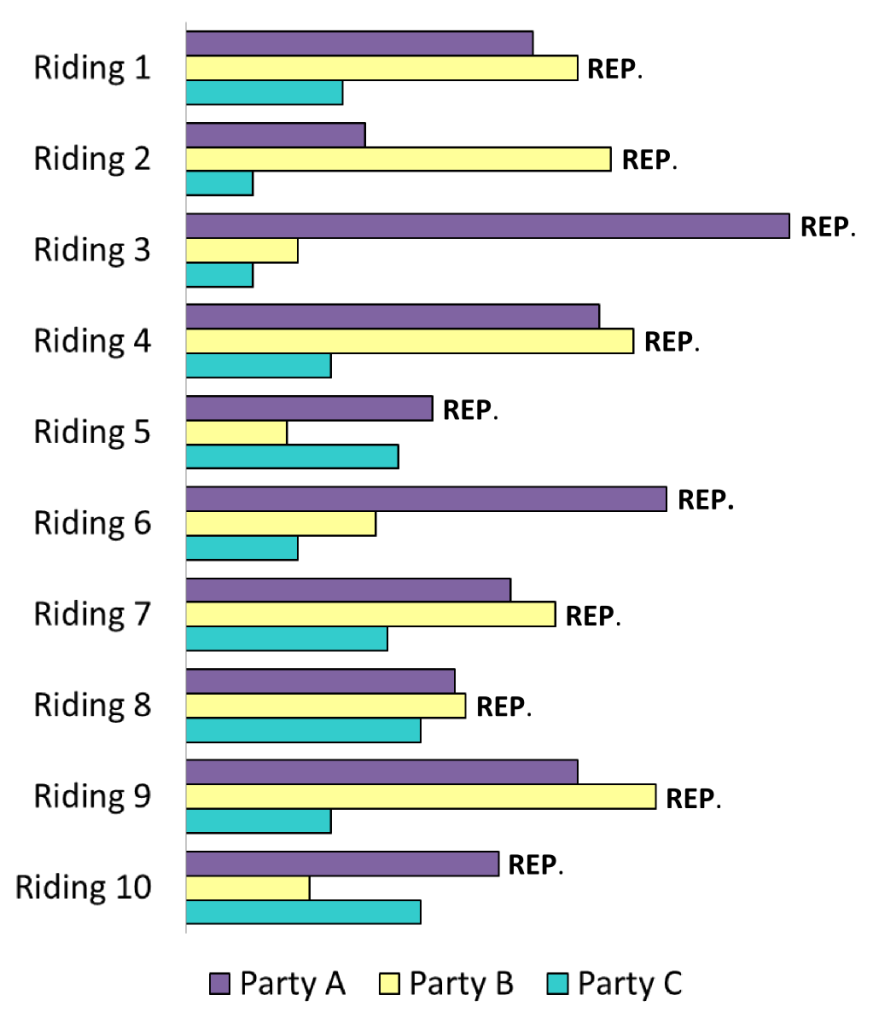

A simple example illustrates who gets elected under a Cooperative Proportional voting system. The example pertains to an imaginary region with only 10 ridings and three parties. The number of votes received by each party in each riding is charted below. A label (REP.) indicates the party affiliation of the candidate who wins the riding and becomes the representative.

Representatives elected at the riding level:

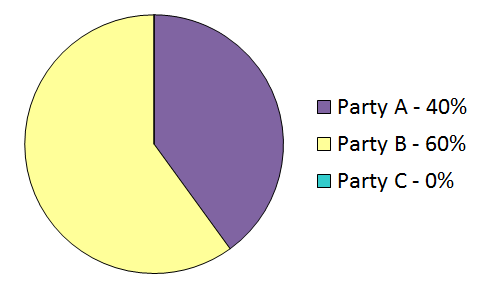

Before we introduce the co-representatives, let’s examine how well the distribution of seats won by the 10 representatives reflects their parties’ actual level of support.

Percentage of ridings won:

Popular vote:

The distribution of seats awarded to the riding winners contrasts sharply with the popular vote. Notably, Party B has a 60% majority of these first 10 seats, yet Party A outperformed them by an 8% margin in the overall vote count. Meanwhile, Party C received an appreciable 20% of the popular vote, but has no seats whatever.

By electing representatives in a First Past the Post manner, a discrepancy emerges between the popular vote and the distribution of seats. To rectify this problem, co-representatives are determined in a way that brings the seat distribution closer to proportionality. This is achieved by giving each party a certain number of top-up seats, enough to bring its overall seat count in line with its actual level of support. The chart below indicates the party affiliation of the co-representative (CO-REP.) elected in each riding.

Elected representatives and co-representatives:

The procedure for determining the co-representatives is explained toward the end of this article. Here, let’s focus on the outcome. As evident from the chart above, the co-representative is often affiliated with the party obtaining the 2nd most votes in a riding, especially for two-way races such as those in Ridings 1 and 4. A party that wins a riding in a landslide is likely to gain both the representative and co-representative positions, as in Ridings 2 and 3.

What’s most important to understand is that even a candidate of the 3rd-, 4th-, or 5th-place party in a riding may become the co-representative if his/her higher placing opponents fail to win top-up seats. In Ridings 7 and 8, the candidate from Party A places 2nd, yet the co-representative position ends up going to the 3rd-place finisher from Party C. This is because the five top-up seats awarded to Party A are automatically given to the candidates in Ridings 1, 3, 4, 6, and 9, all of whom won a larger percentage of the local votes than their counterparts in Ridings 7 and 8.

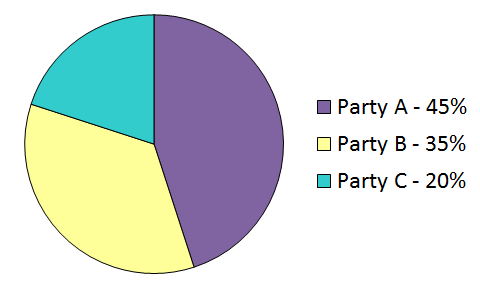

The number of top-up seats received by a party is essentially the number of seats it is owed based on the popular vote, minus the number of seats it wins in the First Past the Post stage. As shown below, the final number of seats won by each party now matches the popular vote.

Percentage of seats won:

Popular vote:

Although Cooperative Proportional would double the number of MPs per riding in Canada, the size of each riding would also double. With half the ridings, the overall number of MPs would remain the same.

Goal #4: The system ensures that the government has MPs from each region of the country

When Pierre Elliot Trudeau and the Liberals won the 1980 election, the party failed to gain a single seat west of Manitoba. Canadians do not want to see large geographic regions thoroughly excluded from the reigning government’s cabinet, especially when many citizens of that region voted for the winning party.

By electing two MPs per riding, not necessarily from the same party, Cooperative Proportional reduces the chance of such geographically polarized results. It is not the only system that improves upon First Past the Post in this regard. STV and MMP also tend to spread out the elected members of the ruling party. By outright eliminating 2nd-, 3rd, and 4th-place candidates, the current First Past the Post system conceals the diversity of political views that exists within most regions.

Goal #3: The system allows you to directly elect MPs who represent your community

We must acknowledge that in the Abacus Data survey, the goal emphasizing community representation ranked two places higher than the goal expressing proportionality. Technically speaking, all proportional voting systems under serious consideration for Canada account for local preferences to some extent. Nevertheless, STV and MMP are often met with skepticism in this regard.

In the case of Multi-Winner STV, voters elect five or so MPs to represent each district. Unfortunately, these districts would be roughly five times larger than the current ridings under First Past the Post. So while all MPs have a regional affiliation, some Canadians may worry that their local communities would receive inadequate attention within their much larger encompassing districts.

In the case of MMP, the ridings remain reasonably small, and voters still elect one MP who is dedicated to their riding. However, there are a number of elected MPs who do not win in any riding, since they receive a top-up seat in a larger region that encompasses a dozen or so ridings. The criticism that arises is that this second group of MPs—the ones with the top-up seats—have lesser responsibilities and incentives to advocate for any particular community. His/her foremost obligation, it is claimed, is to further his/her party’s interests as opposed to supporting Canadians. The claim is debated, but we must acknowledge that many Canadians place great value on an MP’s dedication to a relatively small constituency.

The importance placed on community representatio n has led me to revise the Cooperative Proportional system. Originally, I raised the possibility of a very small 2% threshold applied to individual candidates.

I must admit that a threshold imposed on individual candidates seems perfectly reasonable. […] Any candidate […] who individually holds less than 2% of the votes in his/her riding is simply eliminated.

Now I propose a much stricter 20% rule that takes the place of this 2% threshold. The 20% rule states that the co-representative must have at least 20% as many votes as the representative. If the riding winner receives 60% of the votes, for example, then any candidate with fewer than 12% is eliminated. If the winner receives only 40%, then the other candidates need 8% to stay in the race. The purpose of the 20% rule is to ensure that both MPs in a riding are perceived as having a mandate to speak on their constituents’ behalf. Also, both MPs realize that they must serve their constituents well in order to be re-elected.

Goal #2: The system produces stable and strong governments

It did not surprise me that a desire for “stable and strong” governments ranked high on the survey. But what did surprise me is that the goal of producing majority governments ranked only 10th out of 15 on the list. My perception had been that Canadians by-and-large preferred majority governments for their inherent stability and efficiency in getting bills passed. Since the survey suggests otherwise, how do we interpret the desire for stability and strength?

My interpretation is based on concerns raised about electing “fringe parties that hold the balance of power”5, or “transforming fringe groups into coalition kingmakers”6. Suppose that a formal or informal coalition emerges that includes a number of small parties dedicated to very specific issues. Any one of those parties could threaten to vote against the coalition at an inopportune time, essentially coercing support for their own cause. Of course, opportunistic negotiations can and do take place even in the current system. But with too many small parties holding the balance of power, it seems plausible that a purely proportional system could lead to instability.

The possibility of highly fragmented coalition governments is taken seriously, even by proponents of proportional representation. In fact, proportionality is often moderated in a way that restrains the proliferation of small parties and reduces the power they’re likely to acquire.

One of the simplest ways to moderate proportionality is to impose an election threshold. This is done in a multitude of countries using proportional voting systems. Essentially, a threshold means that any party receiving below a certain percentage of the votes, say 5%, is eliminated and does not receive any seats. Advocates of proportional representation often mention an election threshold as a safe-guard against power-seeking extremists.

Although I am convinced that proportionality must be moderated to some extent to promote stable governments with comprehensive platforms, nation-wide thresholds do not appeal to me. With a 5% threshold, a party receiving 5.1% of the vote would get 17 seats, while a party receiving 4.9% would get zero. In my opinion, this hardly adheres to the principle of proportionality. Furthermore, thresholds can lead to tactical voting, where one votes for his/her 2nd-choice party in order to help them meet the threshold and form a coalition with his/her 1st-choice party.

In place of a threshold, my previous article recommended a 2% buy-in. By choosing to contest a riding, a party implicitly agrees to have 2% of the votes cast in that riding subtracted from its national total. Thus the party must get at least 2% of the riding’s votes just to “break even”. The Conservative, Liberal, NDP, and Green parties would accept this condition and continue to run in every riding. Other parties would have to consider how serious they are about representing particular ridings, as there is a cost to receiving minimal support.

I still believe that subtracting 2% is a reasonable approach, but I would now apply this adjustment within a top-up region consisting of ten or so ridings. Top-up regions are yet another way to moderate proportionality. The idea is that top-up seats are only distributed within a top-up region, so the number of seats won by a small party will often be rounded to zero. Top-up regions have the added benefit of limiting the range of influence of each vote. A vote in one riding may have some effect on the outcome of neighboring ridings, but no effect whatsoever on ridings far away. If contesting any riding within a top-up region, a party will have 2% deducted from its share of the popular vote within the region. The standard methods used to calculate top-up seats will redistribute this 2% in favour of large parties.

Top-up regions limit the geographical area over which a small party can accumulate votes. The 2% adjustment reduces the party’s ability to gain top-up seats. The 20% rule may prevent the party from actually assigning the top-up seats it does receive. These measures should be sufficient to moderate proportionality and maintain stability.

Some of my early ideas for moderating proportionality now seem obsolete. For example, I originally put forward a variant of my system, called Cooperative Half-Proportional, in which top-up seats are distributed amongst parties without subtracting the seats already obtained in the initial First Past the Post phase. This would likely be a mistake. The subtraction not promotes proportionality, but might also produce outcomes that better reflect voters’ preferences at the local level.

Another idea I now dislike is that of limiting the total number of top-up seats to help independents.

Because a fair number of Canadians vote for independents, the total number of top-up seats is likely to be fewer than the total number of ridings. Accordingly, there will be a few ridings where no contender acquires a top-up seat. In these ridings, the 2nd-place finishers become the co-representatives.

It has been pointed out to me that I overstated the level of support typically given to independents in Canada. Furthermore, the subsequently released Abacus Data survey shows that electing more independents is of low priority to Canadians. More importantly, electing the 2nd-place finisher by default may actually create an incentive for parties to place 2nd in certain ridings instead of 1st. Any incentive to lose, no matter how rare, troubles me.

It is clear to me now that the total number of top-up seats distributed to the parties must exactly match the number of remaining seats. Nevertheless, I still believe—based not on evidence but rather on principle—that independents deserve a fair opportunity to be elected. The 20% rule helps in this regard. Suppose that an NDP candidate wins a riding with 47% of the vote, while an independent places 2nd with 43%. The remaining 10% is split 50-50 between the Conservatives and the Liberals. In this case, the Conservative and Liberal candidates are eliminated based on the 20% rule, so the independent acquires the co-representative position by default.

Goal #1: The ballot is simple and easy to understand

Of the 15 goals in the Abacus Data survey, a simple ballot turned out to be the most widely approved. Some proportional systems introduce complexity by allowing a voter to select or rank candidates within his/her preferred party. For example, Multi-Winner STV allows parties to run multiple candidates within each district. To fully support a party, a voter should rank all of its candidates first before proceeding to candidates of other parties or independents. On an Open-List MMP ballot, each party has its own list of candidates within with a top-up region encompassing many ridings. In addition to choosing a riding-level MP, a voter selects one candidate from the list associated with his/her preferred party. While complex ballots give voters greater opportunity to express their personal preferences, it is not clear that Canadians want additional options.

Cooperative Proportional keeps the ballot simple. Voters mark a single ‘X’ in a single circle, just as they do under the current system. The only difference is that there would be two names beside each circle instead of one. Under Cooperative Proportional, MP hopefuls run in teams of two: one candidate and one co-candidate. In any riding, there would be one Conservative team of two, one Liberal team of two, one NDP team, one Green team, one Bloc team for Quebec ridings, perhaps one or two teams for less established parties, and possibly one or two independent teams. Below is an illustration of how the ballot might be laid out.

Ballot Layout:

If a Canadian voter places an ‘X’ beside the Conservative team, he/she is saying the following:

- I want the CANDIDATE from the Conservative party to be elected and represent my riding.

- If possible, I want the CO-CANDIDATE from the Conservative party to also be elected and represent my riding.

- In addition, I want the Conservative party to gain top-up seats so that they may elect more MPs in nearby ridings as well as my own.

The same applies to votes for other parties. Votes for independent candidates help them win locally, but have negligible influence on how top-up seats are distributed amongst the parties.

The Cooperative Proportional ballot is one of the simplest that exists among proportional systems. The German state of Baden-Württemberg uses a system somewhat similar to my proposal, and their ballot is also simple. Under Single-Winner STV, Multi-Winner STV, and Open-List MMP, the voter has more choice but must deal with greater complexity.

Closed-List MMP is an interesting case in which the ballot is simple and highly praised, but the system itself raises concerns. Under Closed-List MMP, voters place one ‘X’ for a party, and one ‘X’ for a local candidate who may be affiliated with a different party. Many Canadians speak longingly of such a ballot, but are less keen on the underlying system which assigns top-up seats based on “closed” lists determined by parties. Open-List MMP allows voters to decide who gets the top-up seats, but this complicates the ballot with additional lists of candidates.

By keeping the ballot simple, Cooperative Proportional satisfies Canadians’ top goal in the Abacus Data survey. But there’s another question: is the system itself simple? Unfortunately, the details concerning who gets elected tend to get complicated in the case of proportional systems, and Cooperative Proportional is no exception. I have tried to make find the simplest procedure that gives all parties and candidates a fair opportunity while ensuring that all votes count. The full procedure is as follows.

Step 1: Every vote received by a two-member team is initially assigned to the candidate.

In other words, the co-candidates start with zero votes.

Step 2: The candidate with the most votes in each riding is elected.

In other words, one seat in each riding is filled in a First Past the Post manner. The remaining steps determine how the other seat is filled.

Step 3: Each winning candidate’s excess votes are transferred to his/her co-candidate.

The “excess votes” include every vote that the winning candidate did not actually need to win the riding. The number is calculated as the votes received by the winning team, minus the votes received by the 2nd-place team, minus one. Once transferred, the excess votes help the co-candidate get elected.

Step 4: Any contender with less than 20% of the winning team’s votes is eliminated.

The “winning team’s votes” refers to the total votes received by the winning team prior to the vote transfer in Step 3. Any team that does not win its riding will see its co-candidate eliminated here, since he/she still has zero assigned votes. The co-candidate of the winning team may or may not be eliminated, depending on how many votes were transferred.

Step 5: If a riding has no contenders able to win top-up seats, the top contender is elected.

This step applies to independents and contenders whose parties failed to receive more than 2% of the popular vote in the top-up region. If all other types of contenders in the riding have been eliminated by the 20% rule, the independent or small-party contender with the most votes is elected by default. This step gives an independent a chance to be elected even if he/she places 2nd in the riding.

Step 6: Top-up seats for the unfilled positions are distributed amongst the parties.

Within each top-up region, top-up seats are assigned one at a time to parties with remaining contenders. The next party to receive each seat is determined using the Sainte-Laguë method, which involves selecting the greatest fraction from a set of fractions. The numerator of each fraction is the number of votes received by a party in the top-up region, minus 2% of all valid votes cast in the region. A party only receives top-up seats beyond the number of seats it has already won. Also, a party cannot have more top-up seats than it has remaining contenders. The total number of top-up seats distributed must exactly equal the number of as-yet unfilled positions.

Step 7: Contenders whose parties have top-up seats are elected from top to bottom.

Within the entire top-up region, the top contender whose party has at least one top-up seat is elected. The top contender is the one with the highest percentage of his/her riding’s votes. The number of top-up seats held by his/her party is then decreased by one. Also, the other contenders in the same riding are eliminated. The act of electing the top contender is repeated until every party has either no remaining top-up seats, or no remaining contenders.

Step 8: Top-up seats are reassigned as needed.

At this point, one or more parties may have top-up seats but no remaining contenders to accept the seats. These top-up seats are reassigned to parties that have no top-up seats but do have remaining contenders. The receiving parties are chosen using the same method as in Step 6. Again, a party receives no more top-up seats than it has remaining contenders, and the total number of top-up seats equals the number of as-yet unfilled positions.

Step 9: Step 7 and Step 8 are repeated until all positions are filled.

Electing one contender at a time, reassigning top-up seats as needed, eventually every co-representative position will be filled.

This procedure is somewhat more complex than that described in my original article on Cooperative Proportional. The original procedure had a flaw in that a party might have had an incentive to place 2nd instead of 1st in one or two ridings. By ensuring the number of top-up seats matches the number of as-yet unfilled positions, the new procedure corrects my original oversight.

Although the procedure has many steps, the steps themselves are reasonably intuitive. I imagine the system could be explained effectively using animations. What’s important is that the ballot remains simple, and the task of marking the ballot does not require detailed knowledge of the full procedure. Voters need only realize that the system respects both their local preferences and the popular vote.

Conclusion

Cooperative Proportional provides what Canadians are looking for in an electoral system. It introduces proportionality without sacrificing the most widely approved qualities of First Past the Post. After introducing refinements to ensure every MP is accountable to his/her riding, the system still achieves my original goals of making every vote count and ensuring that election outcomes are fair.

- David Coletto, PhD, and Maciej Czop. 2015. Canadian Electoral Reform: Public Opinion on Possible Alternatives. Conducted for the Broadbent Institute. URL: http://www.broadbentinstitute.ca/canadian_electoral_reform

- Canadian Electoral Alliance. Trudeau’s response to Proportional Representation (following the Dec. 19, 2014 motion to adopt MMP). URL: http://electoralalliance.ca/justin-trudeaus-response-proportional-representation

- Liberal Party. Policy Resolution 31. URL: https://www.liberal.ca/policy-resolutions/31-priority-resolution-restoring-trust-canadas-democracy/

- Rhys Goldstein. 2015. Cooperative Proportional: A new voting system for Canada. URL: http://rhysgoldstein.com/2015/11/21/cooperative-proportional/

- John Ivison. 2015. Can any government be trusted to pass electoral reform without rigging the process in its own favour? National Post. URL: http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/john-ivison-can-any-government-be-trusted-to-pass-electoral-reform-without-rigging-the-process-in-its-own-favour

- Asher Honickman. 2015. The people need their say on proportional representation. National Post. URL: http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/asher-honickman-the-people-need-their-say-on-proportional-representation

Since initially posting this article, I’ve had a chance to simulate what might have happened in New Brunswick and Alberta this past election (October 2015) had a Cooperative Proportional system been used. At some point I hope to share the results. The exercise has led me to edit the above article as follows:

1. Previously, I suggested that either the D’Hondt method or the Sainte-Laguë method could be used. I now recommend the Sainte-Laguë method, which yielded more proportional results in the case of the New Brunswick simulation.

2. The previous procedure for electing co-representatives made it possible for a party to lose many top-up seats as a consequence of having only one contender eliminated due to the 20% rule. Such a scenario did not occur in the New Brunswick and Alberta simulations, and it might be very rare. Nevertheless, I have slightly modified the procedure such that the number of top-up seats lost by a party in Step 8 should not exceed the number of contenders the party loses in Step 4.

(The previous version of the article is still available as a PDF.)

Not too long ago I too became interested in electoral reform and invented a “new and better” system. It turned out to be very similar to MMP in Baden-Wurttemberg: a single vote for a candidate and top-up seats filled by repechage of unsuccessful candidates in riding contests (by percent vote rather than number of votes). I noticed that as Cooperative Proportional was refined from Canada-wide to 10-seat districts it now looks more similar to 1-vote MMP with repechage.

An interesting feature of the B-W system is that when a riding association nominates a candidate, it names also an alternate. The alternate’s name appears also on the ballot and in the event that a top-up MP dies in office or resigns, the alternate fills the spot.

That is interesting that the Baden-Württemberg proportional system includes alternate candidates on the ballot. It makes perfect sense. By reducing the need for by-elections, the overall distribution of seats should remain closer to the popular vote. Not to mention it saves voters an extra trip to the polling station. Thanks for pointing that out!

It seems that Canadians who try to come up a voting system often end up with something similar to B-W’s form of MMP. Certainly that’s true in both your case and mine. It must be a sign that the B-W system would satisfy a number of commonly stated priorities. It would keep the ballot simple. It would require all politicians to be elected based on their individual votes at the local level. Cooperative Proportional goes a step further by ensuring exactly two representatives per constituency.

Even though Cooperative Proportional ties every MP to a riding, I think there are practical benefits to grouping nearby ridings into top-up regions. For example, New Brunswick (1 top-up region, 5 ridings, 10 seats) would retain full control over who they send to Ottawa. In theory, the whole country could be treated as one top-up region, allowing for a very high degree of proportionality.

Drawing top-up MPs from a district of 5 to 10 ridings (10 to 20 seats in Cooperative Proportional) seems a reasonable choice. One problem with having the whole country as one top-up region (if I have understood the allocation method correctly) is that a judicial recount that changed a winner in Halifax could sent a ripple of changes through the entire country and result in a change of top-up MP in a Victoria riding.

You’ve understood the method correctly. This “ripple” effect is one of my concerns about grouping all of Canada into one top-up region. With top-up regions of 10 to 20 seats, as you suggest, a judicial recount would have dramatically less impact. The outcome of an election would be less proportional, but maybe only slightly less.